Contributed by: Bill Morris

People in story: WILLIAM MORRIS

Location of story: Near Arromanches, Normandy

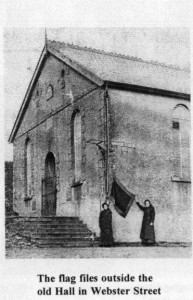

My name is William Morris, my childhood and early years were spent in the mining town of Treharris, South Wales. At the bottom of Webster Street where I lived was the Deep Navigation Colliery and at the top of our street was the Salvation Army Hall.

I joined the Royal Navy during the war and served for a time with Combined Operations in preparation for the Normandy Landing. A few days before the invasion I joined a crew of a converted Thames Barge which was loaded with high octane petrol, bound for the Normandy Beaches. The barge was moored at Itchenor, which is part of the Chichester Harbour.

In the early hours of 6 June 1944 we set off from our mooring with an armada of small landing craft. We were directed to Gold Beach at Arromanches, close to the proposed siting of the Mulberry Harbour. I am unsure of the actual date but some time later we were caught in a severe storm and it became necessary to abandon the vessel. We were taken to a survivor’s camp run by the Royal Marines, at a field close to the ruins of the village of Arromanches. The barge was recovered with the cargo of fuel intact. Much of our time in those days was spent in clearing the beaches in preparation for the Mulberry Harbour.

One day I listened to the shouting of some soldiers disembarking from a Landing Ship Infantry and the accents sounded all too familiar to my ears. They were Welsh and to my ears they came from the mining valleys ! As they moved up the beach I recognised someone from Treharris… I thought I was dreaming as they passed the word back to the Landing Craft. “Tell Fred his brother Bill is up here on the beach!” Fred came running as fast as he could, closely followed by Sergeant Willie O’Neill, who happened to live across the street from us in Webster Street. We stood there staring at each other for ages trying to accept this improbable meeting and were surrounded by others from Treharris.

The Morris tribe were seven children that had survived infancy, my mother having given birth to a total of thirteen. Two girls, Evelyn and Olwen and five boys, Tom, Fred, Ivor, Bill and Glyn. The mining towns of South Wales had endured the full force of the Depression and General Strike of the 1920s and 1930s.

Four of us boys played brass instruments in the Salvation Army Band, namely Fred, Ivor, Bill and Glyn. A little further up the road was the Territorial Hall that offered two weeks holiday, under canvas, to any boys who joined the Unit of the Territorial Army. Many did join along with Fred and Tom, (Tom being the eldest boy of the family).

They were all called up in 1939 and some served with the 5th Welch Regiment. Later on Tom returned to work in the coalmine. Fred’s talent on the trombone was soon recognised and he became a member of the 5th Welch Regimental Band. Part of his duties when on active service meant that he was a medical orderly and stretcher bearer.

Fred was 23 years of age and I was 19 years of age at our momentous meeting in Normandy. I don’t know how long we stood there but at last an officer of the regiment came up to us with a friendly smile and said, “There is a war going on up the road and we should move on”.

It was well known that there was strong resistance at Caen from the Germans and that is where the Regiment were heading. Within a few days I received a letter that Fred had returned to a hospital in England with multiple shrapnel wounds and that Willie O’Neill had been killed in action.

(Resources include a BBC website about stories from World War 2)

Myself and Bill got in touch and he graciously sent me a copy of his wonderful book “More value than many sparrows” He also said that if anyone wants to purchase the book he can arrange it at a discount price of £10 to include postage and packing if ordered through him…just leave a message on here and I will supply Bill’s contact details.

I decided to do an interview with Bill about the time he lived in Treharris and the experiences he had living here before the second world war…here are the results of that interview…thank you Bill for doing this…

Paul:

Did you join The Salvation Army in Treharris, exactly where were they based because there is no sign of them in Webster Street today, how did they raise funds. Did they teach children to play instruments, who were the main people involved, where did they march, was it only Treharris, or did they get to the surrounding villages?

Bill

You were puzzled because there is no sign of the Salvation Army Chapel in Webster Street today and you are perfectly correct because the building had been demolished in June 1978. The Salvation Army sold the site and purchased the premises previously occupied by Cooperative Department Store in Perrott Street. The old site at the top of Webster Street was sold and a bungalow put in its place.

I was last in Treharris for the funeral of Bandmaster Fred Willetts. Fred had been the bandmaster for over 50 Years and the family invited me to speak at his funeral as his lifelong friend. Fred joined the Band when he was about 8 years old. He played cornet and sat next to me on Sunday morning for the meeting. Fred would fall asleep during the sermon and lean his head on my shoulder. He would wake up with a start when we began to play the closing hymn! At that time I was about 13 years of age. The service took place in the Tabernacle Chapel on Saturday 1 September 2007. So many people wanted to attend from all over the land bringing the total number to around 300 persons. I have avoided visiting the site in Webster Street for years because I feel so sad that the building was demolished.

Bandsman Billy Treharris Salvation army

Yes, I did join the Salvation Army as a junior and then joined the senior band. My first visit to the Army is clear in my mind because my sister Evelyn was to be married one year later to James Starkey who lived at number ten Webster Street. From that first visit when I was but four years old I knew that I was going to belong for many years to those lovely people who were my neighbours.

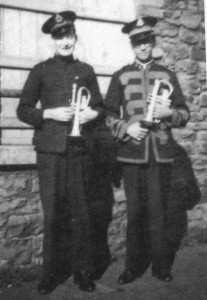

George Knott(left)and Dai Davies (right)

The Salvation Army funding came from the poor people themselves who were members, as well as from collections in the streets and by selling the ‘War Cry’ in the pubs and drinking clubs around Treharris. The Army was highly regarded in Treharris and well supported. The gang of four comprising Glyn, Will, Dai Davies and Billy joined the junior band when I was about nine years old. We were taught to play by Ted Barnes who was Deputy Bandmaster at the time. Ted played the trombone and lived at Cilhaul where we would go to his house to practice. My brother in law Jim Starkey lived with Evelyn in a lovely cottage in Quakers Yard at that time and Glyn and I would go there to be given extra tuition by Jim. Both Ted and Jim would stand behind us and beat out the tune with an old leg of a chair. After a year or so we joined the senior band. You have a photo of the senior band taken around 1927 but this was taken about seven years before we joined them. We marched around all the streets of Treharris and the surrounding villages.

Glyn Morris and Will Davies

Paul:

Leaving school and starting work, what jobs did you have before the war?

Bill

I left school at fourteen years of age in 1938 and the family agreed that I should try to find employment other than in the coalmine. Evelyn and Jim were living at Llandenny where Jim was employed on the GWR as a signalman. They lived in a farm cottage in the grounds of a farm. Mr Evans told me that he knew a young farmer who wanted a farm hand near Raglan. I took the job and lived in for one week only. The farmer was newly married and I was not welcomed in the family home by his wife so I left. I still wanted farm work and replied to an advert for work at Laugharne. The employer was a barrister and the farm was a large manor house up a Long driveway with five house staff and me. I worked with a farm manager and we got on well but after about two months I decided that farm life was not for me. At that time Dylan Thomas was living in the village with his wife and writing some of his works that are still read throughout the world. Dylan Thomas was ten years my senior.

Paul:

Deep Navigation, the pit pond, the colliery itself.What are your memories?

Bill

The magnet of the Deep Navigation Colliery was about to draw me into its net! It was decided that I would work beside Fred in No 2 Pit. Fred worked with a ‘Buttie’ called Tom Jones who lived in Edward Street. That first day was a terrible experience for me, the cage door closed; we were in free fall that juddered to the pit bottom. We then had a long walk, carrying a cumbersome lamp in one hand and a water container, acting as a shield for the person walking behind me.

My Tommy box of food was in my other hand. The long trudge ended when I saw before me the gleaming coal face of black gold. My feeling was of being locked in this blackness all day and then to come up into a blinding light which we call sunshine! Most of my school friends were down in the pit with me and there was a wonderful feeling of comradeship amongst the men and boys.

After the shift one of my friends suggested that we go to the billiard hall where we played a game but my mind was not there. It was facing the fact that tomorrow would be exactly the same as today!

The pit pond was where I learned to swim after almost drowning in the Pandy. My brother Ivor took Glyn and I for a walk around the Pandy one Sunday afternoon. It was out of bounds to us because I was only about six years at the time. I took off one of my shoes and decided to float it as a boat in the water. The shoe started to sink so I reached forward to grab it but I overbalanced and fell in. The water was very deep and I struggled but drifted out towards the middle. It was summertime and people were up on the rocks sunbathing after their swim. Ivor kept shouting ‘Help’ but no one was listening. Eventually some man high up on the rocks heard his cry and dived in to save me. I never knew his name but after I had left home for the Navy years later Ivor found out that he lived in Bedlinog and went to his house to thank him for saving his brother Billy from drowning. The episode caused the older boys in Webster Street to teach us to swim in the pit pond! The pond was the last resting place for our domestic pets so we were in good company! We youngsters were thrown in and had to find our way back to the bank by swimming. If anyone got into difficulties the others would rescue us, after a while.

Paul:

Trelewis, Edwardsville, Quakers Yard, Bedlinog and Nelson… what memories have you of these villages?

Bill

I have many memories of all the surrounding villages because when we were young the four boys used home as a place to eat and sleep. Otherwise we were on the march far away or close to home. Trelewis has happy memories because often we would sit on the mountain behind Webster Street in the summer and look across towards Trelewis. My father had been a Foreman Builder there when some of the new houses were built but we made up our own stories about that terrible place. We called it Stormtown because all of our bad weather came from Trelewis as well as all the bad luck we suffered in our lives. We thought that the inhabitants came from outer space and one day would take over our town.

The four used to visit the chapels at Trelewis on Sunday evenings and we loved the tin chapel where they sung hymns in Welsh. We were so loud and guessed at some of the Welsh words that the rest of the congregation didn’t stand a chance! Edwardsville was another haunt of ours. On Christmas Day the Salvation Army Band would march around all the Treharris streets ending up outside Beechgrove Cemetery. Our Bandmaster was Will Edwards and although he was a fine musician he was not a child psychologist. On Christmas morning the Band would meet in Webster Street at 9 o’clock in the morning to march around and wake everybody up! It was usually so cold that the valves on the instruments would freeze and we needed to use our breath on the valves to release them.

Youngster would join us to sing the carols with the new toys in most streets. We played up quite a lot and Will Edwards would ask us to behave and if we were good one Christmas Day he promised us children a present at the end so we were on our best behaviour. He opened his briefcase at Beechgrove and gave us each two fingers of Kit Kat chocolate! On Easter Day we four used to visit Beechgrove Cemetery in our Salvation Army uniforms and walk around to the graves that had no daffodils. We would collect a few from each grave that had many flowers and share them out until an official came and chased us away!

Between the wars, Bedlinog was known in Treharris, as ‘Little Moscow’ because it was felt so many of the people were communists. There was in Forest Road, Treharris a Pentecostal Church and sometimes the four would attend the meeting on Sunday evening as a change from the Salvation Army. One week they held a mission and were helped by the members of the Pentecostal Church at Bedlinog. There were a number of pretty girls about our age came down from Bedlinog to help with the mission. We used to help at the mission because we fancied the girls but when the mission ended so did the girls and so did we!

Nelson was a favourite place of the four because we went to the cinema there sometimes. The Knott family lived there and we used to call in to see them. I remember the handball pitch in the centre of Nelson which was used regularly by visiting teams.

Paul:

What was The Treharris reaction to the war, people and friends leaving, obviously a lot of Treharris men were required to stay behind to work in the pits, it must have been a worrying time?

Bill

The war meant that things in Treharris would never be the same again. War was declared on Sunday 3 September 1939. The news was given to me by Tom Richards in the shop in Webster Street. Whatever we needed was purchased on the day rather than storing foodstuffs as we do today. A fridge was considered to be the luxury of the rich and famous in the land. I had just come home from the Salvation Army hall at about 12.15 and Tom’s shop was always the centre of news information. Olwen asked me to go across to the shop for gravy browning for the Sunday lunch. Tom announced to me that war had been declared between Britain and Germany. The very news came with a wave of excitement to my mind but I was to learn from experience the horror of war.

The Territorial Drill Hall was along a lane beyond the Salvation Army and many of the boys in Treharris were peacetime Territorial’s. The attraction was a free holiday as Territorial’s when very few of the boys could ever hope to have a holiday any other way. My brothers Tom and Fred belonged and they were soon called up for duty with the 5th Welch Regiment. Although mining was essential work the Terriers were needed as a front line of defence. Many of the older people in Treharris had already lived through the First World War and now they were watching preparations for another war!

There was much weeping as the soldiers left the Drill Hall without knowing their destination. One of the boys phoned home that night to announce that they had only gone to Bridgend where they would be staying for some time. Tom worked the Dump at the pit and he was allowed to return home for essential work. There was a lot of reorganisation at the pit with so many young men gone to war. I worked with my new ‘Buttie’ Roy Williams. Roy was in his mid twenties and we got on well together. Friday was payday and Roy used to take me to ‘Conti’s’ cafe in Fox Street where he paid me my wages and treated me to a hot Vimto. Mr Conti had brought his family from Italy after WW1 and had settled down amongst the community. I always found him to be a gentleman who was kind and considerate to his clients. Because he was a foreign national he was considered be a threat to security and so he was put on a ship with other detainees bound for Canada. The ship was torpedoed in the Atlantic and 805 lives were lost which included Mr Conti. Parliament decided that in future all detainees would be kept in the United Kingdom but it was a bitter blow to Treharris. The black early days of the war with all the bombings of the cities and the fall of France to Germany will always remain with me.

Paul: Did you return to Treharris after the war to live, have you visited over the years, what have you observed?

Bill

In September 1946 I returned from the Far East on the Merchant Navy Troopship having left my ship at Singapore. I was given early release from the Royal Navy because I was to enter the Salvation Army College at Demark Hill in London for training prior to being commissioned as a Salvation Army officer. I was demobbed in early October and was a late arrival at the college. I left home then but Treharris will always be home to me. Over the years I have visited my family but infrequently of late because my brothers and sisters have all died. I still have relatives living in Treharris. Kathleen Morris, my brother Fred’s wife lives in Williams Terrace, Olwen’s son lives in our old house in Webster Street, Tommy’s son Graham and his wife live in Fell Street, David Starkey, Evelyn’s son lives in Edward Street.

I am saddened when I see that many fine old buildings have been demolished. My lovely Salvation Army in Webster Street was replaced by a bungalow; The Square no longer exists as I knew it. The Palace cinema was demolished to be replaced by a grassy slope. I have no way of knowing who is responsible for these alterations but it does nothing for the spirit of old Treharris. Although I have not seen the destruction to the buildings that existed in Cardiff Road I am told that the carnage goes on! The greatest sadness that I have is to see how people have lost much of the fire and fight which was evident between the wars and during WW2.

If only that fire and fight could be revived I have hope for my home town even today.

thanks Bill